|

SPECIAL FEATURE | An historical overview of Macau sites and walks  In the footsteps of Macau's maritime past when the city dominated Far East trade: saints, artists, adventurersIn the 16th century as the world raced to Macau on the coattails of the China trade, grand edifices like 'The Vatican of the East' (top right), were coming up. We explore history and the quirky people who brought it all to life, from art to A-Ma Temple (top centre). Also see our Macau Guide and view our brief Cotai Photo Essay. THE MACAU story really began when Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal “conceived of this incredible idea of making the ocean, beyond which it was believed lay nothingness, into a highway...,” writes Austin Coates in his concise and engaging history, A Macao Narrative. The endeavour was fuelled by a combination of curiosity, adventure, and the need for new trade routes to evade Ottoman encirclement in the Mediterranean. This existential quest led to the rounding of the Cape of Good Hope by Vasco Da Gama and stormy crossings from Africa to Goa, Malacca and eventually Macau. Fast Portuguese caravels — with triangular lateen sails that allowed greater manoeuvrability — dominated the seas while larger ‘Black Ships’, their hulls slathered in waterproofing tar, traded with Japan, passing on illicitly procured Chinese porcelain and silk as well as Portuguese arquebus long guns in exchange for Japanese silver. by the late 16th century, Macau was the fulcrum of all mercantile activity with Imperial China and Japan...

Portuguese 'Black Ship' replica at the Poly MGM Museum (far left), Camoes Garden flowers (centre left) and city views from above the pagoda; Chapel of St Francis Xavier, Coloane (centre right); and bust of poet Luis de Camões at the grotto (far right) This hugely profitable exchange ensured a swift progression from the island wastelands of Liampo and Sanchuang (the first foreign toeholds on the China coast with their squalid blow-me-down shacks) to Macau that was rented as a trading post in 1554 and then secured on a permanent lease in 1557. And it was Macau, not Hong Kong, that formed the initial fulcrum of furious, if furtive, and hugely profitable, mercantile activity with Imperial China and Japan through the 16th century. Gorged on Japanese silver, as Portugal rose to become the dominant sea power controlling trade in the East, so did Macau’s fortunes climb. This astonishing rise was evocatively captured in The Maritime Silk Road exposition at the Poly MGM Museum (now the 'Silk Roads Beyond Borders' exhibition), MGM Macau, a hotel with its own captivating art collection. Entry is free. The Portuguese proved to be great culinary cross-pollinators as well, bringing from South America, corn, potato, sweet potato, chillies, tomatoes, beans and peanuts. The local Macanese cuisine was greatly shaped by these exotic new ingredients. Portuguese poet Luis de Camões celebrated the new-found confidence of a country with a population of barely a million at the time, in the prologue to his epic The Lusiads: “Let us hear no more…of Ulysses and Aeneas and their long journeyings, no more of Alexander and Trajan… My theme is the daring and renown of the Portuguese, to whom Neptune and Mars alike give homage.” This son of Portugal and one-time Macau resident is memorialised at the beautiful Camoes Garden (Jardim de Luís de Camões) draped over a hill opposite St Anthony’s Church (that dates back to about 1580). His bust peers through a grotto atop the floral gardens and tree-lined walks with spaces for exercise and contemplation. The public gardens with their profusion of lush tropical trees from Malacca, are popular with walkers and tai chi enthusiasts. Atmospheric views of Old Macau open up from the blue-tile Yu Hong Pavilion. There are children’s play areas, a library, statues, nurseries, exercise equipment, and a mansion (once the office of the East India Company and now home to the Oriental Foundation).

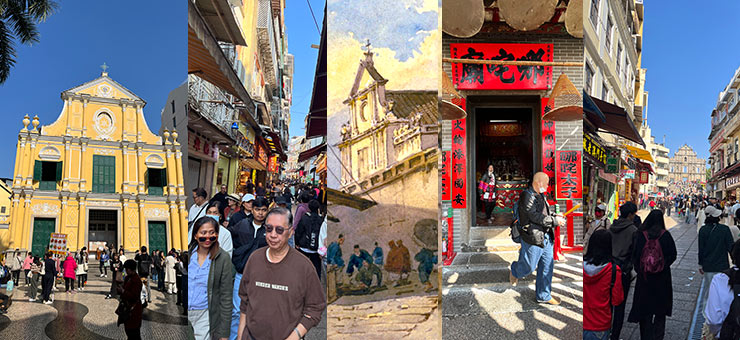

Much photographed yellow-wash St Dominic's Church (far left) built in the Baroque style; crowded alleys leading to St Paul's facade; George Chinnery's painting of St Dominic's (centre, from print) and tiny red emblazoned Taoist Na Tcha Temple A small Protestant chapel and cemetery by the entrance complete the picture. The chapel is named after Robert Morrison, a missionary credited with the first Chinese translation of The Bible, no mean feat. Getting the Protestant cemetery opened in 1821 in an enclave where burials were strictly demarcated and only for Catholics and Chinese, was a another minor miracle. Morrison is buried here along with his wife. Also buried here is famed British artist George Chinnery who introduced Western oil and watercolour techniques to China and vividly portrayed local scenes from 19th century India, Macau and Hong Kong. Much in demand by rich 19th century patrons (including the Jardines) he nevertheless died in debt like many creative sparks of his age. Another name associated with early Macau is adventurer, merchant, fabulist and author Fernão Mendes Pinto who arrived in 1542. His Peregrinacao (Pilgrimage) detailing his adventures is one of the most remarkable travel accounts of the period. According to Mendes, he and his two companions were blown off course in a typhoon and shipwrecked in Kyushu, thus ‘discovering Japan’ in 1543 and opening the way for trade with the West. His claim is hotly contested. The memoir is nonetheless a colourful chronicle of capricious fortune, packed with shipwrecks, captivity and enslavement, discoveries, and work for the Portuguese crown. this redistribution of body parts was an occupational hazard for celebrity preachers of the time...The devout St Francis Xavier made a name for himself around the same time with his proselytizing missions but remained unpopular with traders who saw his austere Jesuit morality as a dampener on the freewheeling piracy and underground trade of the day. It was a direct threat to profit. His planned embassy to Peking — authorised by the Viceroy in Goa — was sabotaged by the commander at Malacca who failed to provision the party. The much thwarted good Saint later passed away in 1552 on barren Sanchuang. According to Fernão Mendes Pinto, three months later when the grave was dug up to transport the body to Malacca, the corpse was “without any sign of corruption“ and the shroud and surplice “were as clean, fresh and sweet smelling as if they had just been washed.“

The Opium House (far left) was used as a warehouse and built after the wars; St Pasul's viewed rom the walk up to Fortaleza do Monte and its canons (centre); the Lisbon-style St Lazarus Quarter with its distinctive yellow buildings. The great man’s remains were distributed between Goa, Rome, Japan and Macau. A bone from his arm found its way to a silver reliquary at the small chapel on the western tip Coloane Island where it is revered till today. In an era of deep religious faith, this redistribution of body parts was an occupational hazard for celebrity preachers of the time. The Chapel of St Francis Xavier (1928) looks over a small well maintained square by the seafront with an unpopulated calmness about it most unlike the frisson of excitement that runs along the Cotai casinos on the reclaimed strip leading to Taipa Island. In the city centre, the broad cobbled Senado Square forms the centrepiece of the UNESCO Historic Centre of Macau World Heritage site. It is lined by ancient buildings like the austere whitewashed Holy House of Mercy (1569) that served as both a medical clinic and a refuge for families of sailors who had perished at sea. It is a museum now. At the other end of the square is the Baroque yellow-wash St Dominic’s Church, dedicated to ‘Our Lady of the Rosary’ who quietly occupies the high altar. It was set up in 1587 by three Spanish Dominicans from Acapulco, Mexico. It attained some notoriety in 1644 when a Spanish soldier caught up in the Iberian Union dissolution ripples (as Portugal revolted against Spain) was put to death at the altar by a pursuing mob. On a more cerebral note, the first Portuguese newspaper in China — A Abelha da China (The China Bee) — was also published here in 1822, making this an unusually versatile space. Today its museum of sacred art displays a variety of ancient icons, artefacts and relics. Just around the side of the church, Rua da Palha branches into the narrow Rua de Sao Paolo that runs north towards Macau’s most sought after site. St Paul’s façade slowly comes into view over the heads of the teeming crowd as people jostle, several darting into side shops for sweet beef jerky and egg tarts before being swept on by the human tide. The imposing and solitary ruin, of Italian design, is set atop a bank of steps and firmly buttressed from the rear. By the time of its opening in 1640 its scale and grandeur had earned it the title, the ‘Vatican of the East’. This was no idle boast. As the first major Catholic church in the Far East it was the mothership — the ‘Mater Dei’ — to spread Christianity (and Western education) into China and Japan. “There was a liberalness, a moderation, which set it [Macau] in a class apart,” writes Coates...The original structure dates to 1580. It caught fire twice and was rebuilt by Jesuits and Japanese Christians using local artisans, the carvings reflecting an eclectic mix — the crucifixion, the Virgin Mary, the Devil, a pantheon of saints, a Portuguese ship, a seven-headed Hydra, temple lions, and prayerful Chinese inscriptions. The wooden nave and transepts perished in yet another epic fire in 1835. In 1597 when the College of St Paul began conferring degrees in Theology and the Arts (with a few students from Japan and India) it effectively became the first Western university in the Far East.

Temple lions (far left) guarding the entrance to the A-Ma complex and pavilions, a hugely popular site; steep street running down to Lilau Square and its fountain (far right); the distinctive Moorish Barracks where Indian troops were oonce billeted in 1874. Its library was said to have a collection of over 4,000 books and manuscripts. Thanks to the Jesuits, by the 16th century, Macau was proud host to a Gutenberg press, the first in the Far East (a replica is displayed at the Macau Museum), which had revolutionised printing in Europe and made The Bible suddenly accessible. English traveller Peter Mundy visited the church in 1637 and was quite taken by the “roffe of St. Paules Church [...and its] New Faire Frontispice”. The church façade was already a recognised marvel of the East. Almost forgotten at the rear western corner of the church, the impossibly tiny Taoist Na Tcha Temple (1888) continues to draw curious visitors and worshippers. Dedicated to a protective deity, it is a testament to the enclave’s historic inclusivity and tolerance. “There was a liberalness, a moderation, which set it [Macau] in a class apart,” writes Coates. One of the reasons may have been the eclectic social mix. In the absence of Portuguese women, Christian marriage partners had to be sought from Malacca and Japan. These Asian women were later joined by Chinese converts. Quite a cultural melange and a huge tempering influence it can be reasonably argued. Added to this was the growing mercantile population focused on silver rather than salvation. To the east of Na Tcha and St Paul’s, steps rise up through the shaded gardens of Parque de Fortaleza do Monte leading to the 17th century Monte do Forte that houses the Macau Museum. An array of canons thrust menacingly through the battlements towards the high-rise glitter of the Grand Lisboa hotel. It makes for a fine Instagrammer spot with grand vistas for orientation. On the other side of the hill, cobbled streets lead down to the St Lazarus Quarter and its bright burst of yellow-plaster buildings with art exhibitions, small shops and the popular Albergue 1601 for fine Portuguese dining. Guia Fortress and Chapel (dating to 1622) and the Lighthouse (1865) above the Jardim Da Flora, are farther to the east, overlooking the Macau Outer Harbour Ferry Terminal. Along the western seafront at Praça do Tap Seac, is another reminder of the city’s turbulent history, the yellow arched former Opium House (1880). While somewhat plain, it makes for an interesting ponder on those heady times. This warehouse is now a clinic run by a charitable group.

The Mandarin's Villa makes for a pleasant stop (far left); St Lawrence's Church with its beautiful vaulted ceiling is one of the oldest on the peninsula (centre left); St Joseph's Seminary (centre) was the main missionary base. It is next to St Augustine's Square (far right). Farther down the west coast at the tip of the Macau Peninsula is one of the oldest places of folk worship in the territory — the A-Ma Temple, built in 1488 to deify Mazu, a young girl said to have been gifted with the powers of weather divination. Fisherfolk believed she had saved countless lives. The spot was called A-Ma Gau (or the Bay of A-Ma), a corruption of which was picked up by Portuguese sailors who started referring to the place as Macau. Serving up a mix of Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism, the temple complex is set up Barra Hill with various pavilions, one dedicated to Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy, a favourite among seafarers. The temple is flanked by the very informative Maritime Museum. From across the square, a pleasant half-hour stroll leads up Rua da Barra and through a warren of tiny lanes to Senado Square. En route, strollers pass the striking mustard arches of the Moorish Barracks (where Indian troops were once billeted in 1874), the eclectic Mandarin’s House (1869), and quaint Lilau Square with its original spring-fed fountain. From here, Rua da Padre Antonio leads to the yellow-wash St Lawrence’s Church (1560), one of the earliest Catholic constructs in Macau. Families of seafarers thronged its steps as they scanned the seas awaiting the return of loved ones, earning the church the Chinese sobriquet, Feng Shun Tang (Hall of Soothing Winds). This historic Macau walk continues to St Augustine Square rimmed by the Dom Pedro V Theatre; St Augustine’s Church (1591); St Joseph’s Seminary (1728), the original launchpad for missionary work in China, Japan and the Far East; the Baroque St Joseph’s Church (1758); and the breezy Library of Sir Robert Ho Tung. This cobbled picture-postcard square offers endless photographic opportunities with flowers abloom amidst historic buildings. It is well worth a browse before the lane drops sharply down to the city centre. As you descend through the narrow streets with scooters buzzing past, gaining glimpses of rooftops and the Largo Do Senado, there are moments when you will feel you have slipped into another time as you relive the history of the Maritime Silk Road that shaped the city’s fortunes, briefly placing a tiny unknown peninsula at the centre of the world's imagination. |